Death in the Ice Part 2: Beechey Island

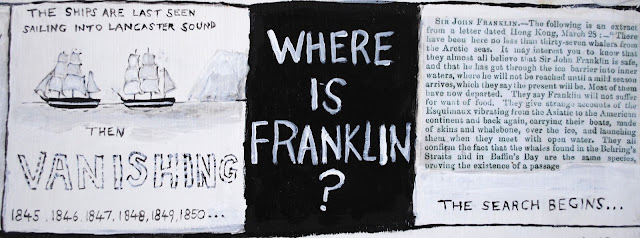

Continuing our journey through Death in the Ice, we leave the Victorian drawing room and enter a big wide dark space, with relics displayed in pools of light. We're back in the Arctic, with the search parties looking for traces of the Franklin Expedition. The search began in 1848, and there would be around thirty expeditions over the next decade.

Among the displays, I was struck by an 1850 Inuktitut phrase book, instructing Naval officers how to ask the Inuit the following questions:

Have you seen any large ships lately?

How many moons since?

Were the ships fishing for whales?

Did they give you any presents?

Are you quite sure you are telling the truth?

Which way did they go when they sailed away?

In 1850, several British and US search ships converged on Beechey Island, where they had the first breakthrough. They found the camp where Franklin spent his first winter in the Arctic.

The most dramatic discovery was of the graves of three members of the expedition, who had died between January and April 1846. From Russell Potter, who has recently visited Beechey Island, I learn that these were found by William Penny's men, who came running back to their ship shouting, 'Graves sir! Graves!'

Two of the grave markers had ominous sounding Biblical quotations on them ('Choose ye this day whom ye will serve' and 'Thus saith the Lord of Hosts, consider your ways'). In his blog, the late William Battersby used these to imagine the sermons that Franklin would have preached at the funeral services.

In the 1980s, the graves were exhumed by Dr Owen Beattie, revealing three amazingly preserved ice mummies.

The excavation was filmed, and shown in the 1988 documentary Buried in Ice, which you can see on Youtube. There's an astounding moment, 35 minutes in, when they open John Hartnell's shirt and see a distinctive Y–shaped incision. 'Son of a bitch!,' they cry, 'He has been! He's been autopsied!'

Yes, John Hartnell was autopsied in 1846, and by none other than Harry Goodsir, who had trained as an anatomist. Stephen Stanley, his superior, was an old fashioned ship's doctor, who would have seen no reason to perform an autopsy (Fitzjames's journal records a lively argument the two surgeons had over the causes of cholera, which Stanley thought was caused by 'impure air').

Owen Beattie found high levels of lead in the dead men's hair and fingernails. He argued that the cause of the Franklin disaster was lead poisoning, from badly soldered tinned food. But these three men all had tuberculosis, and died of pneumonia, not lead poisoning. For all we know, exposure to high levels of lead may have been normal in Victorian Britain. There were no further deaths for over a year, and in May 1847, on the Victory Point record, Fitzjames was able to write 'All well', which he even underlined.

Life size photographs of the three men, lying in their coffins, are shown in a separate section of the gallery, behind a sign saying 'Please be respectful as you enter this space'. At the foot of each man, there is a relic from their burial: John Hartnell's shirt cuff, William Braine's head scarf and the strips of cotton which held John Torrington's limbs in place. A scientific section alongside looks at the evidence for and against various causes of death – lead poisoning, botulism, tuberculosis, scurvy and cannibalism (this certainly did take place later in the expedition, but it's odd to see it included here as a cause of death).

To me, the mystery isn't why these men died, but how so many managed to survive for as long as they did.

Franklin and his crews spent several months on Beechey Island, leaving many traces of their stay, including almost 700 empty tin cans. There was a forge, a shooting gallery, wash houses, a storehouse and even something described as 'a garden'. I was thrilled to see the black pointing hand sign, which I'd only ever seen as an engraving in David C Woodman's book, Strangers among Us. The original sign is now so dark with age that the hand is quite hard to make out.

Some of the searchers believed that the sign pointed to a message, or showed the way that the ships had sailed after leaving Beechey Island. Perhaps it was set up to help sledge parties find their way back to the ships in a snowstorm. But since it was found lying face down in the snow, it ended up pointing at nothing.

The Victorians liked black pointing hand signs. We have a couple in my home town, Brighton.

The most moving relic displayed here is a pair of knitted cotton gloves, which had been left out to dry. Oddly, they are both left handed gloves rather than a pair. In the palm of each, there's a heart, perhaps embroidered by a sweetheart back home.

There were signs that the expedition left Beechey Island in a hurry, for many useful items, such as the gloves, were left behind.

Despite repeated searches of the island, no written records were found. The mystery of where Franklin had gone after leaving Beechey Island would not be solved for another four years.

To be continued...

Comments

Post a Comment